This is the second part in a trilogy of articles about a dynamic UI system we’ve developed at Carousell over the past one and a half years to solve a series of related problems. In the first part, we talked about these problems. This second part will go into more depth about what fieldsets are and some of the properties of the fieldset system.

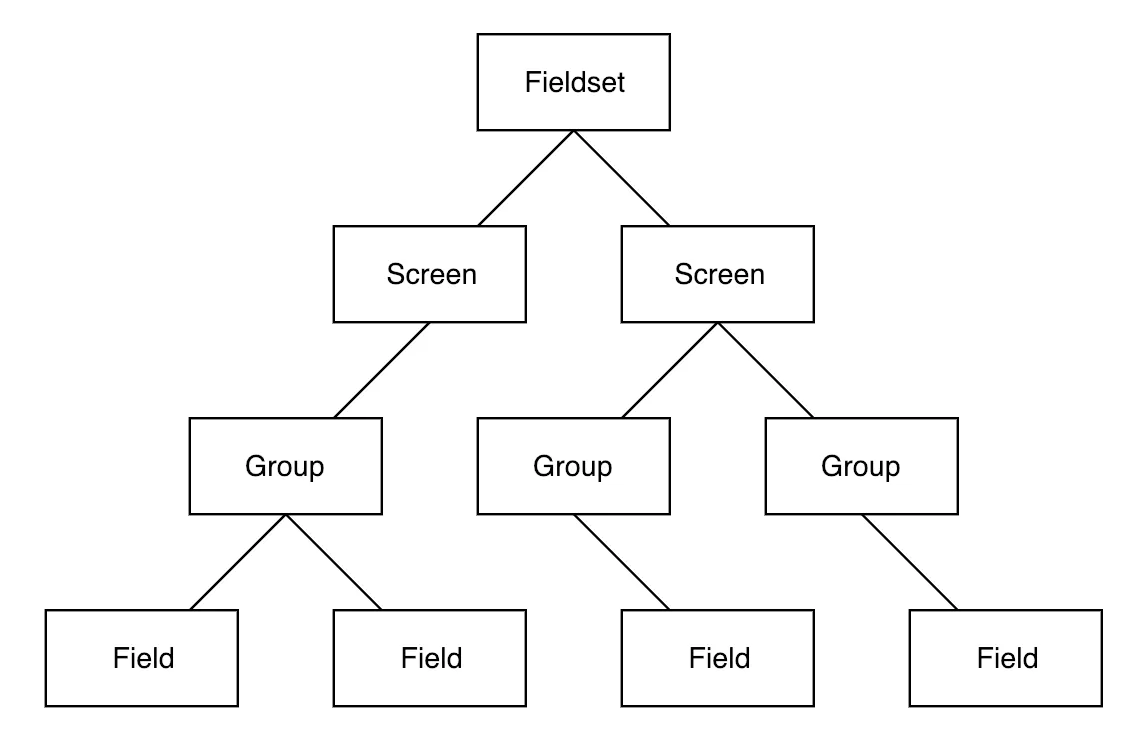

What is a fieldset? A fieldset is a document (in the same sense of a HTML document) with a fixed schema. This schema can be expressed as a hierarchy of entities:

The lowest level of this hierarchy consists of entities called fields. Several fields make up a group, several groups make up a screen, and several screens make up a fieldset.

To draw a connection between the abstract concept of a fieldset and what it represents visually, let’s take a look at the sell form for the iPhone category:

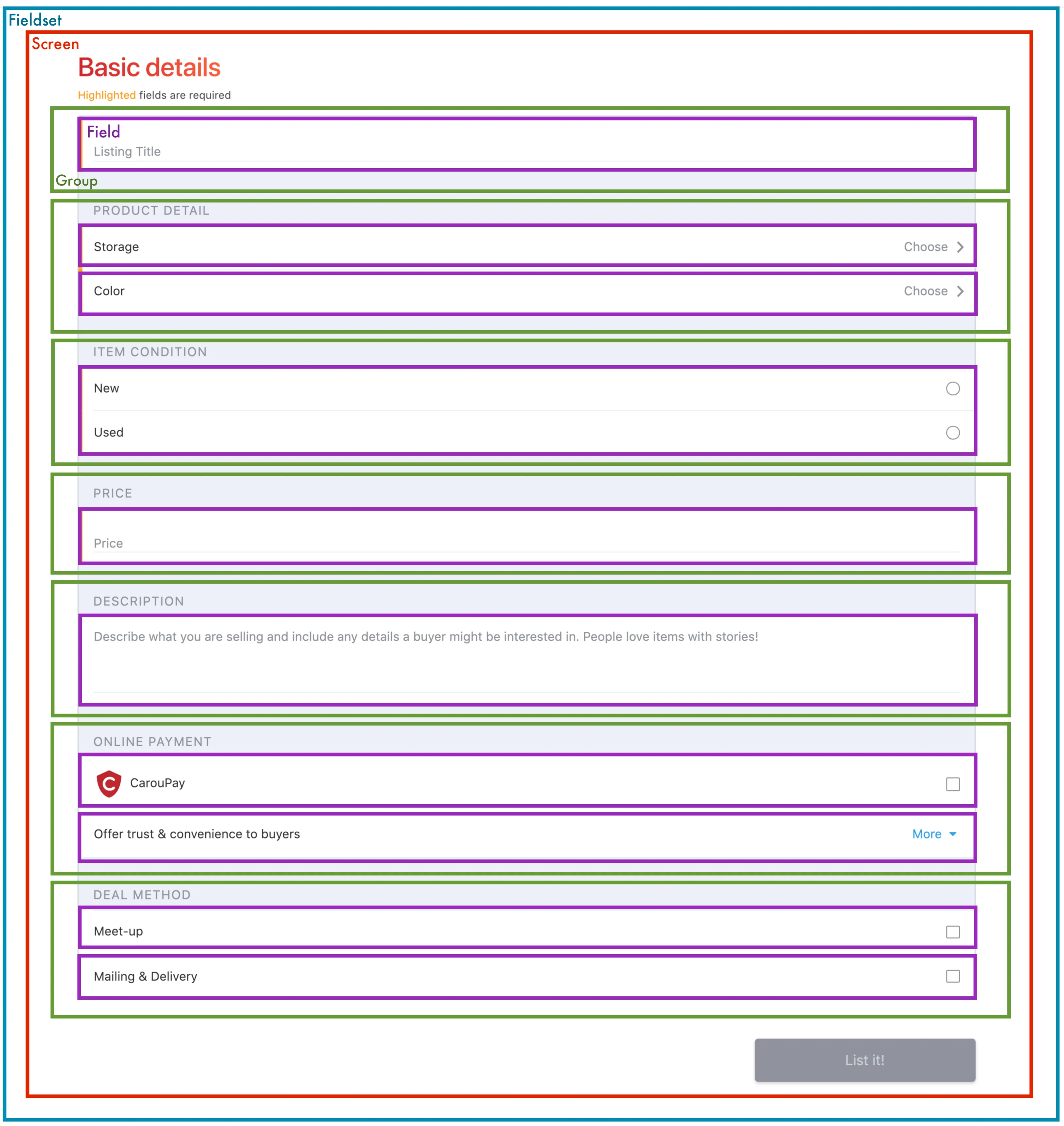

Here is the same sell form, annotated:

Now let’s dive into the annotation to get a better handle on things.

A fieldset, coloured in blue, represents the entire user journey of creating a listing. In this particular journey of selling an iPhone, there is only one screen, which is coloured in red1. Within the single screen exists multiple groups, coloured in green.

In the context of the sell form, each group represents the grouping of related information — information pertaining to product details are grouped together, as is information about various deal methods such as meetup or mailing and delivery. Groups are not just containers for fields either; they have their own data as well2.

Fields, coloured in purple, represent an atomic piece of information to be filled in by the seller. Fields form the bulk of the information within the fieldset, containing information such as UI rules and validation rules that determine the look and behaviour of the component. We will discuss fields in more detail soon, as they represent the core of the Fieldset system.

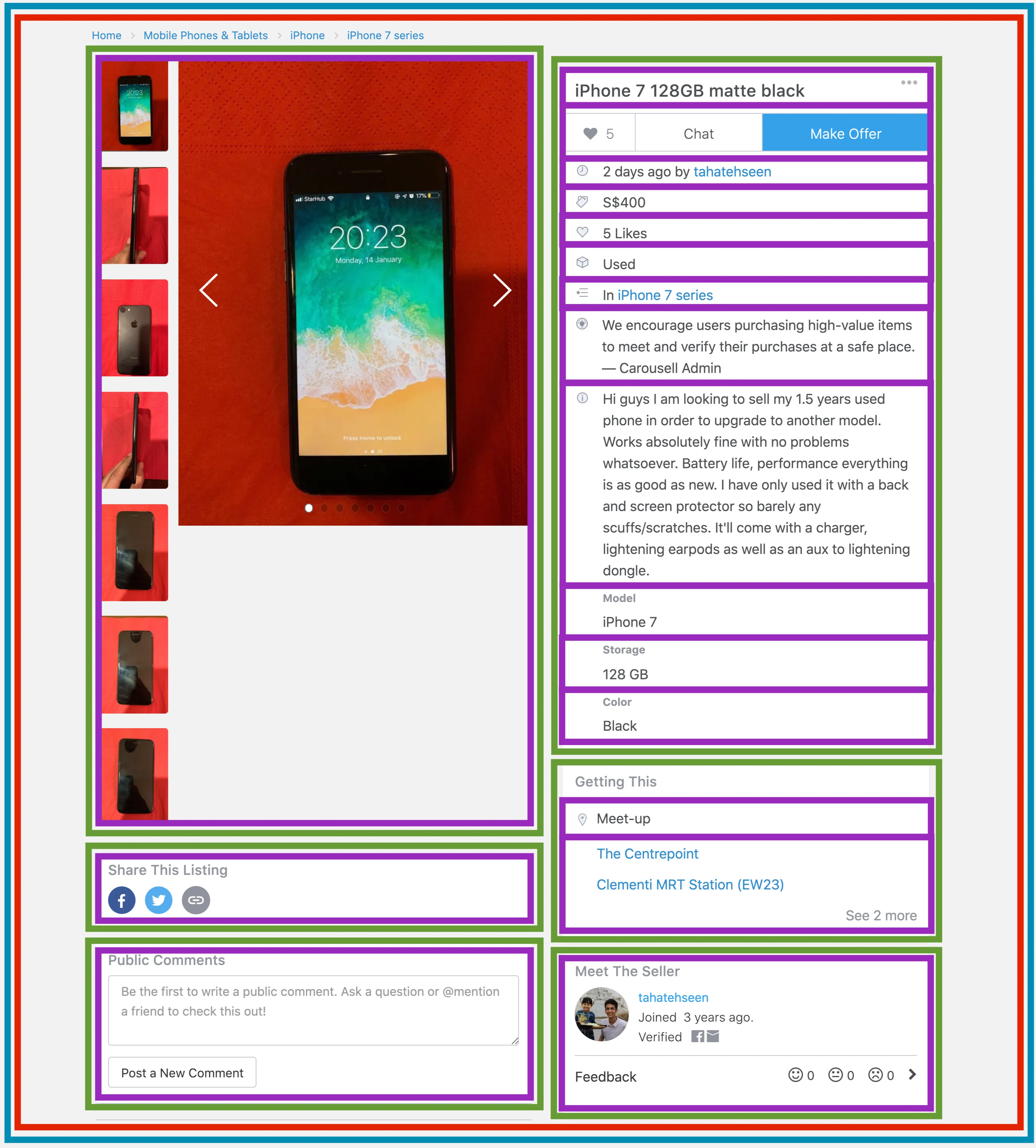

In the following image, we apply the same annotations the listing details page:

On the listing details page, we have a top-level fieldset with a single screen. Within that screen, we can see groups being marked out quite clearly, with the largest group containing the bulk of the listing information. Within this group, each listing attribute such as title, description, model, and storage is represented as a field.

Fieldsets are canonically represented and stored as JSON documents3, a decision we made early on due to its portability across client and server and relative ease of readability and modification.

Here is an abridged version of a sell fieldset:

{

"id": "sell_fieldset",

"screens": [

{

"id": "main_screen",

"groups": [

{

"id": "group_0",

"ui_rules": {

"header": "Basic Details",

"visible": true

},

"fields": [

{

"id": "field_0",

"meta": {

"component": "text",

"field_name": "title"

},

"ui_rules": {

"keyboard_type": "text",

"label": "Title",

"placeholder": "Enter a title for the listing",

"visible": true

},

"validation_rules": [

/*snip*/

]

}

]

},

{

"id": "group_1",

"ui_rules": {

"header": "Other Attributes",

"visible": true

},

"fields": [

{

"id": "field_1",

"meta": {

"component": "text",

"field_name": "brand"

},

"ui_rules": {

"keyboard_type": "text",

"label": "Brand",

"placeholder": "Enter the brand of the product",

"visible": true

},

"validation_rules": [

/*snip*/

]

}

]

},

{

/*snip*/

}

]

}

]

}Let’s take a look at the important bits. The fieldset itself is the top

level object in the JSON document. It contains a screens key (line 3) whose value is an

array of screen objects. Likewise, each screen object has a groups key (line 6), and each

group object has a fields key (line 13, 36). Notice that additional data, represented as meta,

ui_rules, and validation_rules, may be attached at any level as required.

There’s something that sets fields apart from groups and screens. Each field has

an identity — the kind of component it is, as described by the component key

(line 17, 40).

The value of the component key corresponds to a particular visual component. The

example above has 2 fields, both of which are text components. A text component

represents a single-line text input field.

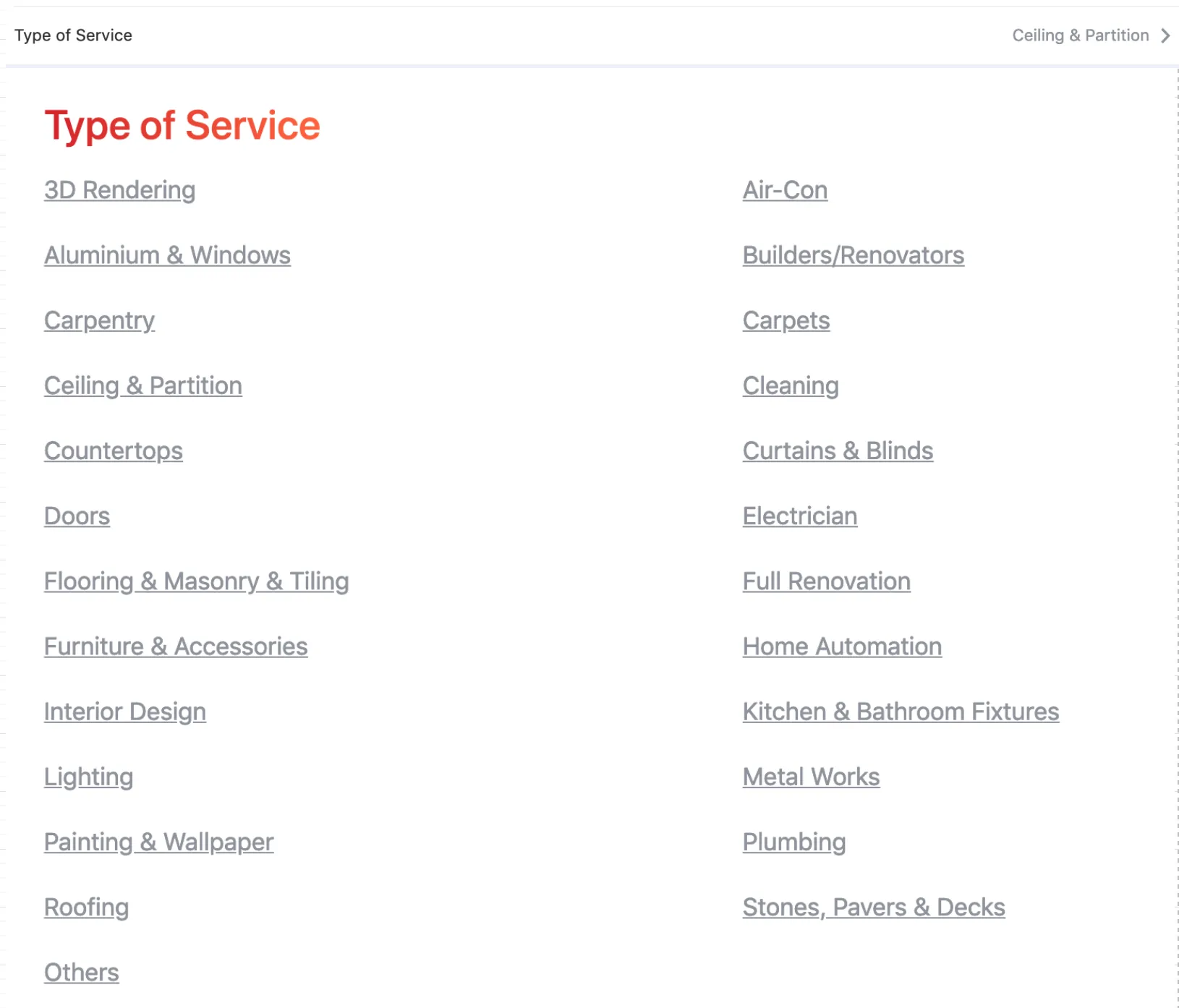

Other common components that are used in form-like fieldsets include picker, a

component which allows selection from a list of predefined options, and radio,

which behaves exactly like its HTML counterpart.

At any point in time, there exists a set of components with which new categories

can be defined, and new features can be implemented. As the pool of components

grows larger, it becomes easier to implement new features, as components can be

reused, even across different journeys. For example, the picker component was

originally written as a component for the sell form, but it is also used in

search filters as well.

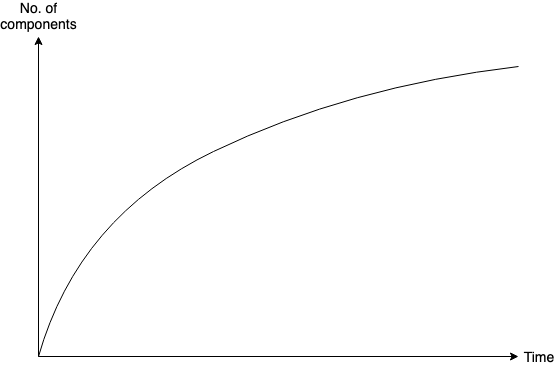

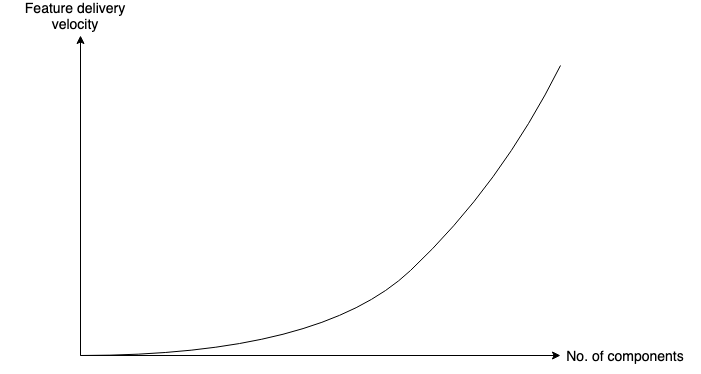

Therefore, one can visualize this scenario with these two graphs:

As time progresses, the chances of needing to implement new components decreases, as new features can be delivered using existing components.

The corollary to this is that as the number of components increase, feature delivery velocity increases since less and less time is spent on developing new components and reusing existing ones. Components developed by team A for feature X can be reused for feature Y by team B. Feature development becomes not just additive in nature, but multiplicative, producing positive externalities for other delivery teams. This is the raison d’etre of the Fieldset system, and a long-term goal that we are striving towards.

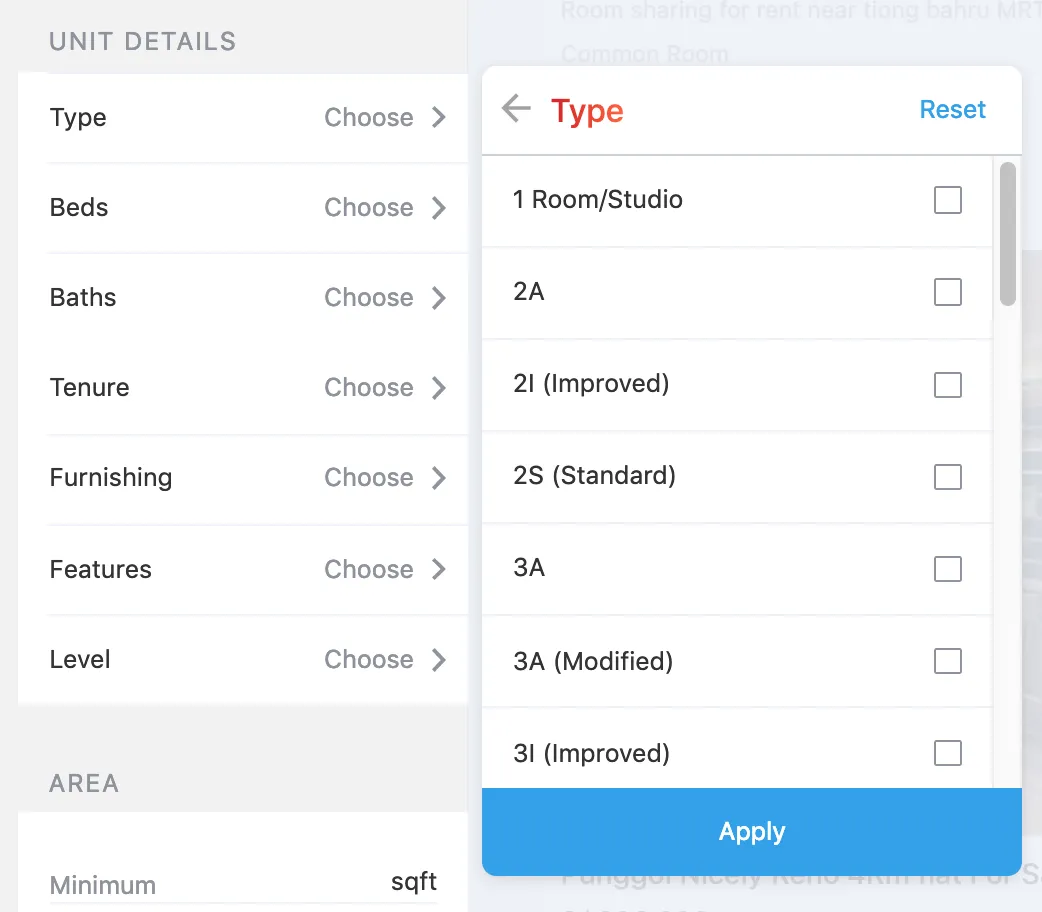

Fieldsets are stored in a Fieldset service. Conceptually speaking, the Fieldset service can be thought of as a giant table that looks like this.

Parameters such as journey, platform, and category_id are self-explanatory.

Others are more interesting; variant allows us to serve different fieldsets

based on which experiment bucket the requesting user falls into, whereas

min_build_no determines the client’s minimum build number required to use this

fieldset. This allows us to devise flexible backward and forward compatibility

strategies. For example, if we wanted to introduce a new component for a product

feature that would only work on newer builds, we would still be able represent

it using older components if needed (as a form of graceful

degradation).

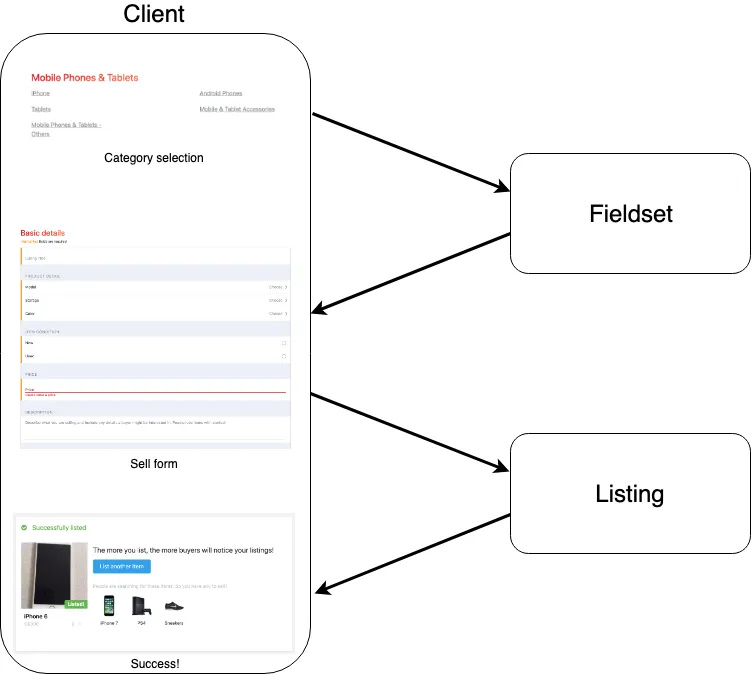

Let’s see a typical request/response sequence between the client and backend services. When a user initiates the process of selling an iPhone, the client makes a request:

GET /api/fieldsets

token: abcd999

journey: sell

category_id: 1234

platform: ios

build_no: 167This request is routed to the Fieldset service, which responds with the appropriate fieldset. Let’s assume that this fieldset sent by the service and received by the client is the example one shown earlier with two fields, title and brand. It proceeds to render these fields accordingly on the screen. Once the user fills in these two fields and hits the submit button, this information is sent, this time to the Listing service, which does two things:

- It performs server-side validation using the fieldset to make sure that the data sent by the client is valid

- If the data is valid, it persists the listing information, and responds with a successful message

The flow described above can be visually represented as such:

Going back to the first part of this series, where we talked about allowing

users to fill in dynamic attributes, the sell fieldset is what enables Carousell

users to — you guessed it — sell. It acts as the schema for listings in a

particular category, dictating what attributes belong in that category, as well

as validations for those attributes (e.g. prices should be non-negative, etc).

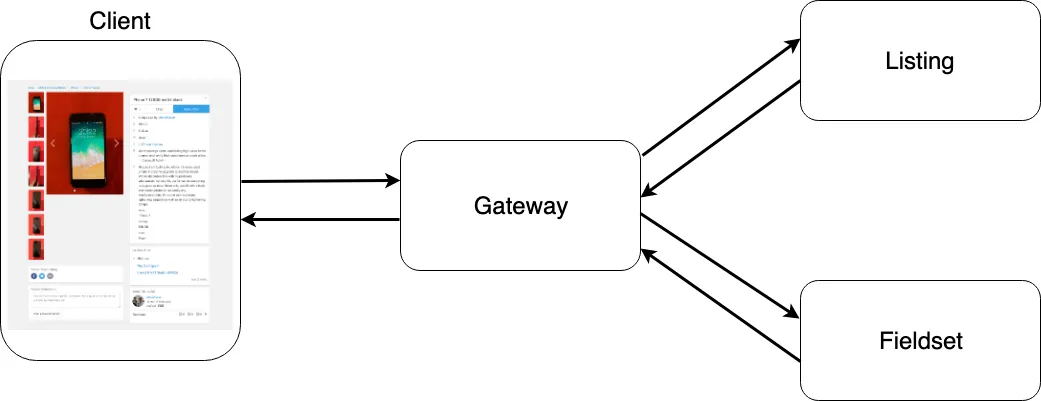

When the newly-created listing is viewed on the listing details page, the client fires a request:

GET /api/listings/123This request goes to a gateway, which fires 2 calls in succession. It first fetches the listing’s data from the Listing service, and then makes a call to the Fieldset service4:

GET /api/fieldsets

token: abcd999

journey: listing_details

category_id: 1234

platform: ios

build_no: 167With the data from both the Listing service and the Fieldset service, the gateway then proceeds to merge the listing data into the fieldset, and returns a fieldset that contains everything required for the client to render the listing details page5.

What does this merging look like? This merging process is fairly complex, with intricate business logic driven by the server side, but generally the process involves inserting listing data at various parts of the fieldset.

Since we’ve saved both title and brand attributes from the sell journey earlier, these are the same attributes we have stored for this listing:

{

"title": "Nice T-shirt",

"brand": "Cool"

}as well as the listing_details fieldset that corresponds to the category that

the listing is in:

{

"id": "listing_details_fieldset",

"screens": [

{

"id": "main_screen",

"groups": [

{

"id": "group_0",

"ui_rules": {

"header": "Basic Details",

"visible": true

},

"fields": [

{

"id": "field_0",

"meta": {

"component": "paragraph",

"value": "",

"field_name": "title"

},

"ui_rules": {

"label": "Title",

"visible": true

}

},

{

"id": "field_1",

"meta": {

"component": "paragraph",

"value": "",

"field_name": "brand"

},

"ui_rules": {

"label": "Brand",

"visible": true

}

}

]

},

{

/*snip*/

}

]

}

]

}The end result would be the insertion of data into the respective fields:

{

"id": "listing_details_fieldset",

"screens": [

{

"id": "main_screen",

"groups": [

{

"id": "group_0",

"ui_rules": {

"header": "Basic Details",

"visible": true

},

"fields": [

{

"id": "field_0",

"meta": {

"component": "paragraph",

"value": "Nice T-shirt",

"field_name": "title"

},

"ui_rules": {

"label": "Title",

"visible": true

}

},

{

"id": "field_1",

"meta": {

"component": "paragraph",

"value": "Cool",

"field_name": "brand"

},

"ui_rules": {

"label": "Brand",

"visible": true

}

}

]

},

{

/*snip*/

}

]

}

]

}This is what the client sees and uses to display the listing details page to the user.

In this second part, we’ve taken a bird’s eye view of the Fieldset system, using

the sell and listing_details journeys and their interplay as examples. Fieldsets

are used in more than just these two user journeys; search filters, search

results, and many other parts of the app use fieldsets to achieve server-driven

dynamicity as well, using the same concepts and interactions as described here.

The next and last part of this series of articles will highlight some other parts of the system that we didn’t manage to cover here.

#Footnotes

-

One can imagine that selling more complex may require multiple pages, which would logically be represented as multiple screens. ↩

-

Notice that some of the groups have headers such as Online Payment, or Deal Method. These texts are appropriately stored at the group level. ↩

-

These days, the fieldset storage system is evolving in a way that this is not necessarily true anymore, but JSON remains a first-class representation of a fieldset. ↩

-

In actuality, we don’t forward the token as is — authentication is performed just once in the gateway and the token is resolved into a User entity which is then used in the rest of the call path. ↩

-

There are more sources of data than just the Listing service. Depending on what components the fieldset has, the gateway may make calls to other services as needed. For example, if the fieldset contains a comments component, then a call would have to be made to the Comment service to fetch the list of comments for this listing. ↩